A Roadmap to Improve Maternal Health in the United States

Learn About a Special Issue of the Journal of Women’s Health

By Dr. Janine A. Clayton

The wealthiest nation in the world is also the most dangerous place in the industrialized world to be pregnant, but it doesn’t have to be this way. With guidance from—and the collaborative efforts of—many partners, we can decrease the Nation’s high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality (MMM). A recent special issue of the Journal of Women’s Health (JWH)—spearheaded by my colleague Samia Noursi, Ph.D., NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) Associate Director for Science Policy, Planning, and Analysis—takes an in-depth look at this public health crisis and proposes a new research agenda.

A Largely Preventable Problem with Significant Disparities

More than 50,000 women experience a life-threatening complication related to pregnancy or delivery (i.e., severe maternal morbidity [SMM]) every year. About 700 women die as a result of those complications, and about 60% of these deaths are preventable. Black women and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women have rates of maternal mortality that are about two to three times higher than those of White and Hispanic women.

The status quo is simply unacceptable. The biomedical community needs to better uncover the root causes of and best practices and policies to address MMM in the United States. Eliminating knowledge gaps in key areas will propel our ability to dramatically reduce avoidable incidents of MMM, as well as bolster the safety of pregnancy and childbirth for all women. With these goals in mind, the special issue addresses four questions:

- Why are some populations at higher risk for MMM?

The gaps in MMM data for some vulnerable groups—including AI/AN women, those with disabilities, and transgender and gender-nonconforming patients—are concerning. Pregnancy surveillance and research must be more inclusive; otherwise, we will not be able to identify the factors that put these women at risk. Where there are sufficient data available, investigators need to more thoroughly research the root causes of higher rates of MMM for specific populations, including Black women and those age 35 or older.

- How can we prevent pregnancy complications and their long-term effects?

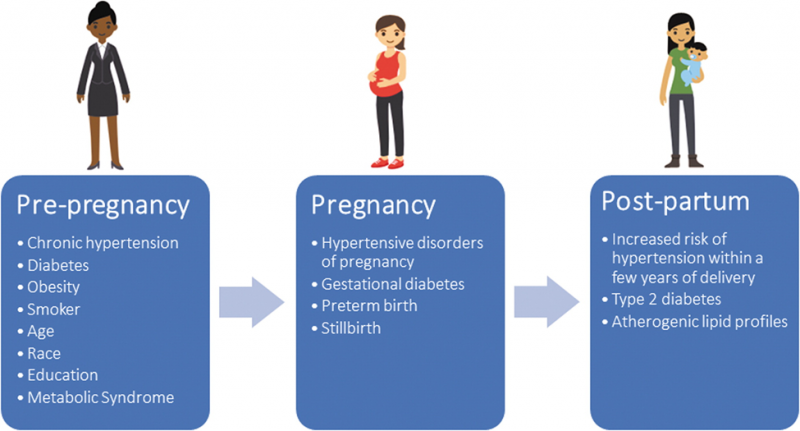

Pregnancy complications can pose acute and long-term health risks. Please see ORWH’s informational MMM booklet for an overview of some of those long-term effects. To create a future free of preventable instances of MMM, we need additional research to increase our understanding of chronic conditions, their effects on pregnancy complications, and the resulting long-term health outcomes. Multiple articles in the JWH special issue outline how we can build the knowledge base to improve the management of these conditions during pregnancy—including cardiovascular disease, pain, sleep-disordered breathing, problems regulating blood glucose, immunity and infection, and perinatal depression. Additionally, the influence of intimate partner violence (IPV) on pregnancy-associated deaths from homicide, suicide, and drug overdose is explored, and policy and practice actions to support pregnant women experiencing IPV are provided.

- How can we improve the safety and quality of maternity care?

Our path to saving women’s lives also requires a research focus on the critical external factors that affect pregnancy and delivery, including the significant gains made when health systems adopt evidence-driven practices, such as protocols to improve obstetric safety.

- What are the external factors that affect maternal health?

Social determinants of health (SDOH) influence the health of all women and could have an even greater impact on pregnant women. SDOH influence root causes of persistent MMM disparities, including environmental stressors, access to care and adequate nutrients, provider-held implicit biases, and countless other factors that influence risk for pregancy complications. However, there are potential solutions in the form of changes to practice and policy.

and postpartum periods. (Varagic et al., 2021, J Womens Health (Larchmt), 30(2): 178-186)

Work to Turn the Tide

The journey toward reducing MMM has already begun with the NIH Implementing a Maternal health and PRegnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE) initiative. Co-led by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), ORWH, and the NIH Office of the Director, IMPROVE supports interdisciplinary research to reduce MMM in the United States—with a focus on the leading causes (cardiovascular disease, infection, and immunity) and contributing health conditions and social factors. NIH awarded more than $7 million to support 36 projects in 2020, with additional research opportunities for 2021. Other funding specifically addresses racial disparities in MMM. As the pandemic continues, NIH is raising awareness on the importance of addressing COVID-19 and maternal health.

These are just some of the many initiatives in NIH’s robust response to reduce MMM in the United States, but more work remains. As the special issue suggests, clinicians and health care professionals can do the following:

- Listen to women; they know their bodies and they know when something is wrong.

- Follow guidelines for pregnancy and postpartum care from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Learn more about addressing implicit and explicit bias when providing care to women.

- Adopt safety bundles from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.

- Apply their knowledge of local maternal health by becoming involved in maternal mortality review committees and joining perinatal quality collaboratives.

In addition to the path laid out for researchers in the JWH special issue, everyone who cares about promoting healthy pregnancy can do something to reverse the trends in MMM. It can be as simple as listening to and supporting women to ensure that they are as healthy as possible before, during, and after pregnancy or as involved as helping them get the necessary care throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period. Everyone can learn the warning signs of complications to help a pregnant friend or loved one or yourself get urgent medical attention if needed. If you are pregnant, you can also provide information to the PregSource research project, a free, confidential website that seeks to help researchers better understand pregnancy by inviting people to share their stories. With collaboration, reducing instances of MMM is achievable.

• The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health’s website: https://www.womenshealth.gov

• ORWH’s MMM web portal, which is a centralized location for NIH’s MMM resources: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/maternal-morbidity-and-mortality

• NICHD’s information on MMM and research resources: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality

• The IMPROVE initiative’s webpage: https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/improve-initiative