What are Sex & Gender?

And why do they matter in health research?

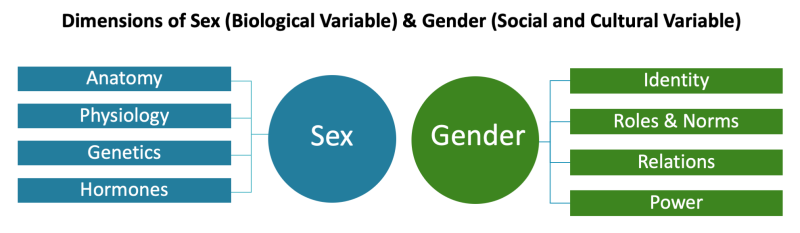

Understanding sex and gender is critical to understanding human health and disease. Although “sex” is often incorrectly thought to have the same meaning as “gender,” the terms describe different but connected constructs. Sex and gender shape health independently as distinct factors, as well as interactively through the many ways in which they intersect and influence each other.[1] It is important to understand the differences and interactions between sex and gender to better understand how they affect health and why they are important in medical practice and health research. [1]

Sex

Sex is a multidimensional biological construct based on anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormones. (These components are sometimes referred to together as “sex traits.”)[2] All animals (including humans) have a sex. As is common across health research communities, NIH usually categorizes sex as male or female, although variations do occur. These variations in sex characteristics are also known as intersex conditions.[3]

Importance of Considering Sex as a Biological Variable in Health Research

Scientists have observed important sex differences across key pathways and processes, such as how the body fights disease (immune system), processes pain (nervous system), and maintains heart health (cardiovascular system).[4] A growing body of health research demonstrates how these sex differences can influence a person’s vulnerability to disease, experience of symptoms, and response to treatment. (Learn more by taking ORWH’s free e-learning course “Bench to Bedside: Integrating Sex and Gender to Improve Human Health.”)

Until recent decades, however, the vast majority of clinical research was conducted with exclusively or predominantly male participants. In addition, most preclinical research with animal and cell models—used to inform our knowledge of human biology and disease—studied almost exclusively male cells or male animals. Despite this narrow approach, the research findings and medical treatments developed from this knowledge were often (and sometimes continue to be) assumed to apply to the whole population.[5]

This systemic lack of female representation (as well as omissions of transgender and intersex populations and persons with variations in sex characteristics) at all stages of the research process has resulted in gaps in our medical knowledge. This evidence gap continues to affect the quality of care patients receive—contributing to delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis for female patients.[6] In addition, the underrepresentation of female participants in clinical studies and the lack of sex-based analysis of data have led to medications that have lower efficacy and greater toxicity for female patients.[7]

Since 2016, the NIH Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV) has helped ensure NIH-funded research rigorously addresses sex as a factor in health and disease.[8]

Gender

Gender is relevant only for research with humans (not other animals). Gender can be broadly defined as a multidimensional construct that encompasses gender identity and expression, as well as social and cultural expectations about status, characteristics, and behavior as they are associated with certain sex traits.[2] Understandings of gender vary throughout historical and cultural contexts.

A person’s gender identity (e.g., woman, man, trans man, gender-diverse, nonbinary) is self-identified, may change throughout their life, and may or may not correspond to a society’s cultural expectations based on their biological sex traits. For example, a person with typical female (sex term) sex traits may or may not be a woman (gender identity). Although gender is often portrayed and understood in Western cultures using binary categories (man or woman) and is often assumed at birth based on a person’s sex traits, many cultures throughout history have recognized a diversity of forms of gender identity and gender expression (how a person communicates their gender to others through behavior and appearance).[2]

Gender roles and norms are a society’s cultural expectations and perceptions about how a person of a certain gender should behave, act, or express themself. Gendered relations are interpersonal interactions and group dynamics that are shaped by individual and societal concepts of gender. These relations are embedded in interpersonal relationships, social structures, and larger systems of power such as political, economic and cultural institutions.

As a domain of gender, power describes the structures and systems of inequity that are based upon gender and which reproduce, shape, and constrain opportunities and experiences for individuals and groups – for example, structural sexism, gender-based violence, and patriarchy.[9] Gender equality (the absence of gender-based discrimination) and gender equity (ensuring every person has access to care, services, and opportunities tailored to their unique needs, circumstances, and goals) are key to addressing health disparities and advancing health for everyone.

Importance of Considering Gender as a Social and Structural Variable in Health Research

A person’s gender can affect their physical and mental health and well-being in many ways and is an important factor in understanding the health of all individuals. For example, gender inequalities in a society have been shown to limit girls’ and women’s access to health services.[9] Gender norms and roles (such as cultural expectations and definitions of masculinity) influence the willingness and likelihood of boys and men to seek health services.[10] Gender norms, gender roles, and gendered power relations (such as a society’s perception of “women’s work” or “a woman’s role”) contribute to the disproportionate burden of caregiving duties borne by women and women’s vulnerability to negative health impacts associated with caregiver stress.[11]

Our Understanding

The NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) is committed to advancing research relevant to the health of all women and all people assigned female at birth. More broadly, the study of how sex and gender influence health and disease is central to the NIH mission of enhancing health, lengthening life, and reducing illness for all people. Together with others in the NIH community, ORWH is committed to advancing the consideration of sex and gender factors in scientific research as critical for rigorous and responsible science and for establishing a future in which every person can receive safe, effective, evidence-based medical care.

Our Programs, Resources, and Initiatives Related to Sex & Gender

ORWH has spearheaded and supported several policies, resources, programs, and initiatives to promote awareness of and research on sex differences and to advance the health of women through research.

Learn more about the Influences of Sex and Gender in Health and Disease

Learn more about the History of Women’s Participation in Clinical Research

Explore free E-Learning Courses About Sex & Gender

Learn about the NIH Sex as a Biological Variable Policy and NIH Inclusion Policies (Inclusion Across the Lifespan Policy and NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research)

Learn more about the Gender and Health Scientific Workshop

Explore ORWH Signature Research Programs & Funding Opportunities for Researchers:

- Specialized Centers of Research Excellence on Sex Differences (SCORE)

- Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH)

- U3 (Understudied, Underrepresented, and Underreported) Administrative Supplement Program

- Sex and Gender (SAGE) Administrative Supplements Program

- The Intersection of Sex and Gender Influences on Health and Disease (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Galvanizing Health Equity Through Novel and Diverse Educational Resources (GENDER) Research Education Program (R25)

Learn more about NIH’s sexual and gender minority–related research on the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office webpage.

References

Krieger, N. (2003). Genders, sexes, and health: What are the connections—and why does it matter? International Journal of Epidemiology, 32(4), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg156

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. [White paper]. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424

Note: (1) Intersex individuals are estimated to make up approximately 1.7% of the population, although some estimates may vary, depending on clinical definitions. (2) Transgender individuals who may have undergone gender-affirming surgery may also have sex traits that do not conform to a single sex.

Grimstad, F., Kremen, J., Streed, C. G. Jr., & Dalke, K. B. (2021). The health care of adults with differences in sex development or intersex traits is changing: Time to prepare clinicians and health systems. LGBT Health, 8(7), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0018

Klein, S. L., & Flanagan, K. L. (2016). Sex differences in immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16, 626–638. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.90

Fauchon, C., Meunier, D., Rogachov, A., Hemington, K. S., Cheng, J. C., Bosma, R. L., Osborne, N. R., Kim, J. A., Hung, P. S., Inman, R. D., & Davis, K. D. (2021). Sex differences in brain modular organization in chronic pain. Pain, 162(4), 1188–1200. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002104<

Walker, C. J., Schroeder, M. E., Aguado, B. A., Anseth, K. S., & Leinwand, L. A. (2021) Matters of the heart: Cellular sex differences. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 160, 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.04.010

Arnegard, M. E., Whitten, L. A., Hunter, C., & Clayton, J. A. (2020). Sex as a biological variable: A 5-year progress report and call to action. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(6), 858–864. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8247

Geller, S. E., Koch, A. R., Roesch, P., Filut, A., Hallgren, E., & Carnes, M. (2018). The more things change, the more they stay the same: A study to evaluate compliance with inclusion and assessment of women and minorities in randomized controlled trials. Academic Medicine, 93(4), 630–635. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002027

Sloan, M., Harwood, R., Sutton, S., D’Cruz, D., Howard, P., Wincup, C., Brimicombe, J., & Gordon, C. (2020). Medically explained symptoms: A mixed methods study of diagnostic, symptom and support experiences of patients with lupus and related systemic autoimmune diseases. Rheumatology Advances in Practice, 4(1), rkaa006. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkaa006

Sims, O. T., Gupta, J., Missmer, S. A., & Aninye, I. O. (2021). Stigma and endometriosis: A brief overview and recommendations to improve psychosocial well-being and diagnostic delay. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158210

Geller et al. (2018) cited above [5].

Zucker, I., & Prendergast, B. J. (2020). Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biology of Sex Differences, 11, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00308-5

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2001). Drug safety: Most drugs withdrawn in recent years had greater health risks for women (Report No. GAO-01-286R).

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-01-286r

Clayton, J. A., & Gaugh, M. D. (2022). Sex as a biological variable in cardiovascular diseases: JACC Focus Seminar 1/7. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(14), 1388–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.050

Arnegard et al. (2020) cited above [5]

Heise, L., Greene, M. E., Opper, N., Stavropoulou, M., Harper, C., Nascimento, M., et al. (2019). Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. The Lancet, 393(10189), 2440–2454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X

Smith, J. A., Watkins, D. C., & Griffith, D. M. (2021). Reducing health inequities facing boys and young men of colour in the United States. Health Promotion International, 36(5), 1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa148

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health. (2021, February 12). Caregiver stress. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/caregiver-stress#references